Our exploration of the relationship between pinfire cartridges and the United States continues with a look at Allen & Wheelock and Ethan Allen & Co.

Ethan Allen was in the firearms and cartridge industry for nearly 40 years beginning in 1832. Many other articles and books cover his business relationships in much more detail than I will go into. This article will only take a look at the time periods where he was making pinfire cartridges.

In the early 1860s Ethan Allen filed for a patent on what would become known as his lipfire cartridge. His patent was initially denied because examiner thought they were too similar to the pinfire cartridges; specifically, the ones described in Eugene Lefaucheux’s 1854 revolver patent filed in England by patent attorney John Henry Johnson. Allen responded that the pinfire cartridge was well-known in the United States and that his lipfire cartridge was an improvement in many ways such as being gastight, waterproof, and less dangerous. He mentioned the dangers of unintentional detonations of pinfire cartridges when dropping them. The patent office agreed with his remarks and noted that other than the fact that they were both cartridges there were practically no other similarities. Even though Allen believed his lipfire cartridges were superior to pinfire cartridges he realized that there was still money to be made from them.

In March of 1862, the Frankford Arsenal was growing tired of the excuses and lack of deliveries of pinfire cartridges by Christian Sharps so they sought out a third supplier. Allen & Wheelock (which was the business name the company went by when it was owned by Ethan Allen and his brother-in-law, Thomas P. Wheelock) was subcontracted by William P. Wilstach & Company, of 38 N. 3rd St in Philadelphia, to manufacture 1,000,000 pinfire cartridges to fulfill their contract with the Frankford Arsenal.

Their cartridges were made very similarly to C.D. Leet’s with the lead plate being placed into the bottom of the case. The main different is that Allen’s have the percussion cap toward the very bottom while Leet’s were in the middle. On May 31st Allen & Wheelock delivered 202,800 cartridges which were described as unsatisfactory. Major Laidley stated that out of 48 cartridges 10 did not fire. And the ones that did fire had issues with too much gas blowing out near the pin hole and issues with the case bursting.

On June 30th and July 31st W. P. Wilstach delivered the rest of their 1,000,000 cartridges which had no complaints. Allen & Wheelock then contacted General Ripley asking to directly supply the government more pinfire cartridges but the Frankford Arsenal did not require any more from them.

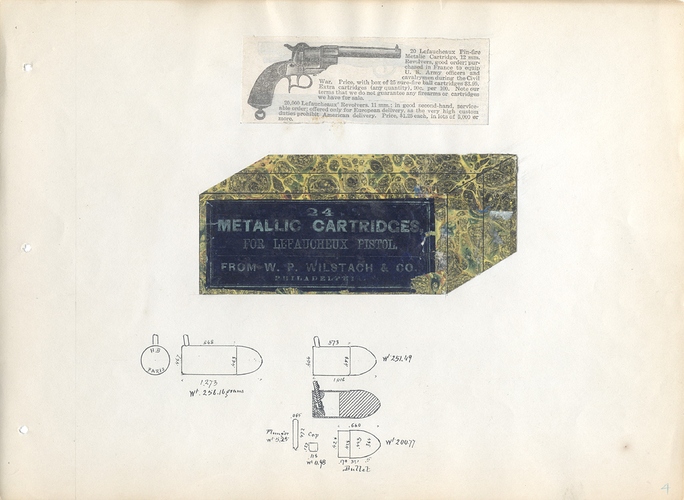

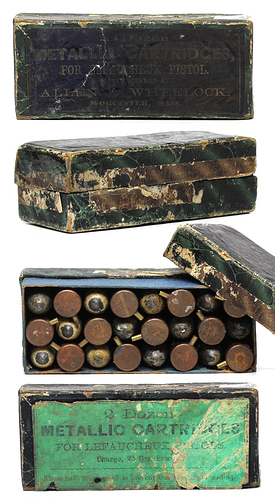

Above is an image of the boxes furnished by W.P. Wilstach. This is an original label and outer paper from a box that was saved and recorded by Brigadier General John T. Pitman. Below, there is also a full box pictured by Allen and Wheelock that leads me to believe that while making the pinfire cartridges for use in the American Civil War, or shortly after their contract expired they also sold cartridges for civilian use. Now this box is extra interesting though because it originally had the green label overtop of the blue label. This label specifies that the cartridges in the box have greased bullets and contain 25g of powder. It also does not mention their company name anywhere on the label. My guess is that these were potentially sold to the government either as part of the W.P. Wilstach contract or maybe even to another agency in some other unknown contract.

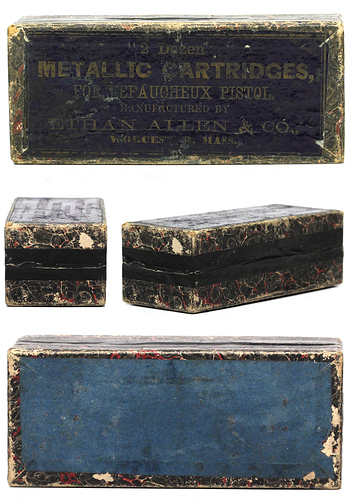

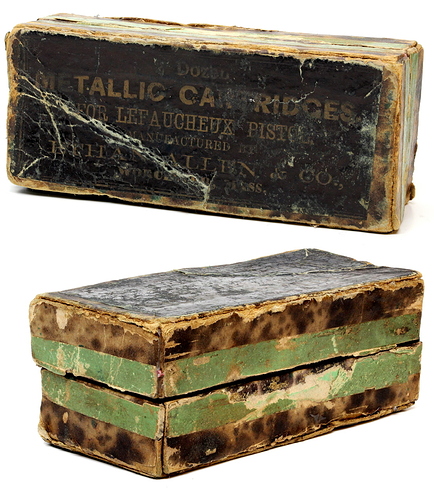

In 1864 Thomas Wheelock died so in early 1865 Allen brought his sons-in-law, Henry C. Wadsworth and Sullivan Forehand into the business and renamed it to Ethan Allen & Co. The company kept this name until Allen died on January 7, 1871. Some time during these 6 years they continued to make pinfire cartridges for retail. The full, sealed box and the opened box below are examples of the boxes made during this timeframe.

References and Further Research:

National Archives. various correspondences.

Thomas, Dean. Round Ball to Rimfire Part Three. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2003.

Barber, John L.. The Rimfire Cartridge in the United States and Canada. Tacoma, WA: Armory Publications, 1987.

Curtis, Chris C.. Systeme Lefaucheux. Santa Ana, CA: Armslore Press, 2002.

Originally published at: https://aaronnewcomer.com/allen-wheelock-pinfire-cartridges/